When did whopping become obligatory before large numbers?

I first noticed it in my students' essays ("Shakespeare wrote a whopping 38 plays" and the like). But since then I don't think I have ever failed to see whopping inserted where attention to a large number was intended to be drawn. Why, just this morning I read that "a whopping 23,000 applications" had been submitted to the Ontario Power Authority for a green retrofit program. And while surfing the web earlier I saw this fearsome headline: "Worst Milkshake Packs A Whopping 2010 Calories"!

Sometimes, the adjective is used in irony (I see someone entitled their blog post "A Whopping TWO New Jerseyans Sign Up for Obamacare Benefits"), but as often as not whopping is inserted with all apparent sincerity, even in serious journalism and scholarly writing. This despite the fact that the Oxford English Dictionary labels its use colloquial or vulgar.

It's like the expression piping hot. People just like to put that word piping in before hot, especially at the end of recipes, where the aspiring cook is enjoined to serve the dish p— h—. The phrase has the reassurance of ubiquity; it may be assumed to be safely idiomatic.

The word whop (first attested in the 16th century) means "to strike with heavy blows; beat soundly, flog, thrash, belabour (a person or animal; rarely, an inanimate object." The OED also deems whop in its various senses colloquial or vulgar.

Whopping, as a participial adjective meaning "abnormally large or great; 'whacking,' 'thumping,'" is first attested in 1625. In 1818, Walter Scott wrote with sartorial enthusiasm in Rob Roy, "What a wapping weaver he was, and wrought my first pair o' hose." Curiously, none of the citations listed in OED place whopping with a number.

I wonder if, in the minds of some (no, a great many) writers, whopping has come to corner the intensifying-adjective-before-big-number lexical market. Perhaps I could suggest a few competitors of a higher register: impressive (as in "Ad Spend on Social Networks Gains Impressive Half-Point in Share") perhaps; or colossal ("Bill Adds Colossal $2 Billion to Deficit"); or, if you're hyperbolically inclined, astronomical ("Fourth Quarter Profit Soars an Astronomical 244%").

Come to think of it, the possibilities are endless. "Profits Shrink by a Crushing 40%"; or "House Sells for Mouth-Gaping $14 Million"; or "Cat Weighs in at Shriek-Inducing 40 Pounds".

But now I've come to a realization. Sometimes, in writing, a vulgar colloquialism is exactly what's called for. Time for a whopping 2010-calorie milkshake.

Monday, September 27, 2010

Sunday, September 26, 2010

Good News

I learned this week that the Boldprint Graphic Novel series has won the 2011 Learning Magazine Teacher's Choice for Children's Book Award. I am the author of four titles in the series — Castaway Island, Kingdom of the Snow Cat, Operation Fly South, and Turtle Rescue.

The series is published jointly by Rubicon Publishing and Oxford University Press. It had previously won the 2010 Texty Award for Textbook Excellence from the Text and Academic Authors Association.

It seemed like the kind of news that might merit a blog post!

The series is published jointly by Rubicon Publishing and Oxford University Press. It had previously won the 2010 Texty Award for Textbook Excellence from the Text and Academic Authors Association.

It seemed like the kind of news that might merit a blog post!

Saturday, August 21, 2010

The Etymology of Perkedel

I was browsing yesterday in Tap Phong (a wonderful shop on Spadina Avenue) and saw a kind of thermos flask called a Qingcheng Coffee Fot [sic]. This reminded me of a theory I have concerning the etymology of perkedel.

A perkedel is defined in my 1963 Malay-English dictionary as "minced meat." But most Singaporeans would think of a perkedel as a fried patty made not just of minced meat but also potato and onions. I've heard it referred to as a "cutlet" (somewhat quaintly, to my ear). If you order a "Royal Flush" from the very popular nasi lemak stall at Adam Road hawker centre, you'll get a perkedel along with your otak-otak and your deep-fried chicken wing. When I was a schoolgirl I used always to get a perkedel along with my mee siam in the school canteen. It was what I dreamed of through the morning, and it got me through Chinese and math. Bagus or what!

But I digress. Last week we were visiting friends in Copenhagen, and the conversation turned to food (naturally). I asked my hosts what they thought the national dish of Denmark was. They made various suggestions, among these liver paste with fried mushrooms and bacon (and, you know, it's quite nice!), but everyone agreed that frikadeller was the thing. Frikadeller are (according to Wikipedia), "flat, pan-fried dumplings of minced meat." I've never eaten any, but they look in pictures very like perkedel.

Of course, it's most likely that the word would have entered Malay through Dutch, and indeed the Dutch do have something called a frikandel, defined unappetizingly by Wikipedia as a "long, skinless, dark-coloured sausage that is eaten warm."

I don't know anything about the phonemic structure of Malay, but it seems to me that originally at least it must have lacked an /f/ phoneme. The F section in my dictionary is only a page and a half long, and about ninety percent of those words are listed as being of Arabic or Persian origin. Many other loanwords that began in the original languages with /f/ or /v/ would have been pronounced with an initial /p/ (though the only example I can find at the moment is panili for vanilla).

Add to this the commonplace metathesis of /r/ and the vowel, and frikadel becomes perkedel. It's a little strange to me that our perkedel resemble Danish frikadeller more closely than the Dutch frikandellen (though, given the description of the latter quoted above, perhaps this is something we can be thankful for); and the monumental Singlish Dictionary by Jack Lee doesn't mention an etymology for perkedel (which he spells begedel), but I am quite sure it is the same word!

I'm probably not the first to think of this (indeed, my hubby is standing on the stairs claiming that he was), but no matter, it was a good excuse to think about eating.

A perkedel is defined in my 1963 Malay-English dictionary as "minced meat." But most Singaporeans would think of a perkedel as a fried patty made not just of minced meat but also potato and onions. I've heard it referred to as a "cutlet" (somewhat quaintly, to my ear). If you order a "Royal Flush" from the very popular nasi lemak stall at Adam Road hawker centre, you'll get a perkedel along with your otak-otak and your deep-fried chicken wing. When I was a schoolgirl I used always to get a perkedel along with my mee siam in the school canteen. It was what I dreamed of through the morning, and it got me through Chinese and math. Bagus or what!

But I digress. Last week we were visiting friends in Copenhagen, and the conversation turned to food (naturally). I asked my hosts what they thought the national dish of Denmark was. They made various suggestions, among these liver paste with fried mushrooms and bacon (and, you know, it's quite nice!), but everyone agreed that frikadeller was the thing. Frikadeller are (according to Wikipedia), "flat, pan-fried dumplings of minced meat." I've never eaten any, but they look in pictures very like perkedel.

Of course, it's most likely that the word would have entered Malay through Dutch, and indeed the Dutch do have something called a frikandel, defined unappetizingly by Wikipedia as a "long, skinless, dark-coloured sausage that is eaten warm."

I don't know anything about the phonemic structure of Malay, but it seems to me that originally at least it must have lacked an /f/ phoneme. The F section in my dictionary is only a page and a half long, and about ninety percent of those words are listed as being of Arabic or Persian origin. Many other loanwords that began in the original languages with /f/ or /v/ would have been pronounced with an initial /p/ (though the only example I can find at the moment is panili for vanilla).

Add to this the commonplace metathesis of /r/ and the vowel, and frikadel becomes perkedel. It's a little strange to me that our perkedel resemble Danish frikadeller more closely than the Dutch frikandellen (though, given the description of the latter quoted above, perhaps this is something we can be thankful for); and the monumental Singlish Dictionary by Jack Lee doesn't mention an etymology for perkedel (which he spells begedel), but I am quite sure it is the same word!

I'm probably not the first to think of this (indeed, my hubby is standing on the stairs claiming that he was), but no matter, it was a good excuse to think about eating.

Tuesday, June 22, 2010

More Suffix-fu Part II

In my previous post, I noted that smile and smirk, tell and talk, and steal and stalk are all pairs that feature the suffix known as k-diminutiva. In other words, to smirk is to make a little smile, to talk is to tell a little, and to stalk is to indulge in a little stealing.

These pairs have of course diverged from one another semantically: a smirk is now a particular and unpleasant sort of smile, while stalking someone is not the same as stealing from them. Yet in these pairs the relations of meaning are still transparent to us.

Not so much in the pair well and walk, both, according to Partridge, related to Latin volvere, "to roll or cause to roll." The word well here comes from Old English weallan (meaning "to well, surge, or boil") and is the verb we use in expressions such as my eyes welled up with tears. The rolling here seems to be in the eddying currents of water in motion; we might think of cookbooks that direct us to bring water "to a rolling boil."

The rolling in walk is at first glance harder to explain. Old English wealcan meant "to revolve, roll, or toss," with the nice figurative sense "to reflect or revolve in one's mind." The ambulare sense of the word did not come in until Middle English, with walken. Even Partridge has a little trouble identifying the precise trajectory of the semantic leap: "the ME sense 'to walk' has perh derived from the OE senses—from the idea 'to walk with a rolling motion' (as a sailor does)."

My feeling, however, is that anyone who has ever used an elliptical machine is quite well acquainted with the rolling motion of walking. I don't suppose that Partridge (who died in 1979) ever had a health club membership, but he mightn't have had to think about a sailor's gait to make sense of this problem if he had ever got on an elliptical trainer.

And since I'm already rambling dementedly here, I'll also add that when I trained under a Zen teacher during my year in Madison, WI (a wonderful place), I had to learn a style of walking called hojo, which involved moving forward with one's hips on a horizontal plane. It was very difficult to master, and was apparently how swordsmen had to walk to achieve optimal balance and poise. But the thing that struck me as I was struggling with hojo was how very "roll-y" my gait became as I tried to keep my hips from bobbing up and down.

I told my Zen teacher all about well and walk of course; I think he was mildly interested.

These pairs have of course diverged from one another semantically: a smirk is now a particular and unpleasant sort of smile, while stalking someone is not the same as stealing from them. Yet in these pairs the relations of meaning are still transparent to us.

Not so much in the pair well and walk, both, according to Partridge, related to Latin volvere, "to roll or cause to roll." The word well here comes from Old English weallan (meaning "to well, surge, or boil") and is the verb we use in expressions such as my eyes welled up with tears. The rolling here seems to be in the eddying currents of water in motion; we might think of cookbooks that direct us to bring water "to a rolling boil."

The rolling in walk is at first glance harder to explain. Old English wealcan meant "to revolve, roll, or toss," with the nice figurative sense "to reflect or revolve in one's mind." The ambulare sense of the word did not come in until Middle English, with walken. Even Partridge has a little trouble identifying the precise trajectory of the semantic leap: "the ME sense 'to walk' has perh derived from the OE senses—from the idea 'to walk with a rolling motion' (as a sailor does)."

My feeling, however, is that anyone who has ever used an elliptical machine is quite well acquainted with the rolling motion of walking. I don't suppose that Partridge (who died in 1979) ever had a health club membership, but he mightn't have had to think about a sailor's gait to make sense of this problem if he had ever got on an elliptical trainer.

And since I'm already rambling dementedly here, I'll also add that when I trained under a Zen teacher during my year in Madison, WI (a wonderful place), I had to learn a style of walking called hojo, which involved moving forward with one's hips on a horizontal plane. It was very difficult to master, and was apparently how swordsmen had to walk to achieve optimal balance and poise. But the thing that struck me as I was struggling with hojo was how very "roll-y" my gait became as I tried to keep my hips from bobbing up and down.

I told my Zen teacher all about well and walk of course; I think he was mildly interested.

Wednesday, May 19, 2010

More Suffix-fu Part I

A long time ago (in a former life, almost), I was writing a research paper on the origins of the English word smile. I had wanted to find out why it was that English, unlike other European languages, had completely different words for laugh and smile. Compare, for instance, French rire et sourire, German lachen und lächeln.

I don't believe I turned up an answer, but I did find out something very interesting. Our smile never made an appearance in English until the 13th century (as a loan from Scandinavian); previous to that, the Old English smearcian (now our smirk) had served.

Now, it so happens that smile and smirk are both related to Latin mirari, "to wonder at." I found this out by looking at Eric Partridge's Origins: A Short Etymological Dictionary of Modern English. (There are many very surprising cross-references to be encountered in this volume. Look up walk, for example, and you'll be directed to "See VOLUBLE, para 7." Check out gymnasium and you'll be asked to "See NAKED, para 4.")

But if smile and smirk are cognates of mirari, where does the -k in smirk come from? It is a diminutive suffix known in Germanic philological circles as "k-diminutiva." This pair, smile and smirk, has parallels in tell and talk; steal and stalk; and even well and walk.

I'll write more about well and walk in my next post, but it's worth noting that k-diminutiva also lies behind the suffix -ock, as found in hillock, bullock, buttock, and, yes, bollocks.

I don't believe I turned up an answer, but I did find out something very interesting. Our smile never made an appearance in English until the 13th century (as a loan from Scandinavian); previous to that, the Old English smearcian (now our smirk) had served.

Now, it so happens that smile and smirk are both related to Latin mirari, "to wonder at." I found this out by looking at Eric Partridge's Origins: A Short Etymological Dictionary of Modern English. (There are many very surprising cross-references to be encountered in this volume. Look up walk, for example, and you'll be directed to "See VOLUBLE, para 7." Check out gymnasium and you'll be asked to "See NAKED, para 4.")

But if smile and smirk are cognates of mirari, where does the -k in smirk come from? It is a diminutive suffix known in Germanic philological circles as "k-diminutiva." This pair, smile and smirk, has parallels in tell and talk; steal and stalk; and even well and walk.

I'll write more about well and walk in my next post, but it's worth noting that k-diminutiva also lies behind the suffix -ock, as found in hillock, bullock, buttock, and, yes, bollocks.

Thursday, May 13, 2010

Asphalt and Groceries

A few years ago, my friend Veronica started ranting at me about Americans' pronunciation of grocery. "They all say groshery," she said. Since then, I can't help but hear this pronunciation everywhere, even on National Public Radio. I'm not sure how widespread it is or that it is just American; I think I have heard it in Canada too, but in a city like Toronto it's hard to say where people are from.

I don't know how this pronunciation arises. Perhaps in moving from a back vowel [o] through an alveolar sibilant [s] and in preparing itself for the liquid [r], the mouth can't help but tend towards producing a palatal fricative. Or perhaps the e after the c is "fronty" enough to produce palatalization. I don't know. But once you notice people saying "groshery," you start to hear it everywhere. And it begins to strike you as a form of gaucherie.

No better is "ashphalt." But here I think we are seeing folk etymology at work. In other words, some folks are a little stymied by the word asphalt (it is rather opaque), and since the stuff is sort of black and smelly, they have decided that the first syllable is really our friendly and familiar English word ash.

Incidentally, asphalt has been around in English since the 14th century, which is much earlier than I would have guessed. The OED cites John Trevisa's 1398 definition of Asphaltis: "glewe of Iudea is erthe of blacke colour and is heuy and stinkynge."

Folk etymology is a fairly common agent of linguistic change. Sometimes it happens when a word is introduced from a foreign language—the above is an example of this, as is sparrowgrass from asparagus.

At other times, a native word has an obsolete element no longer understood by speakers and another, more transparent form is substituted—for instance, bridegroom, from Old English brydguma (compare German Bräutigam), where the second element guma, meaning "man, hero," had ceased to be understood by the 16th century and was replaced by groom, meaning "lad." We might still be toasting the bride and goom if this hadn't happened!

I don't know how this pronunciation arises. Perhaps in moving from a back vowel [o] through an alveolar sibilant [s] and in preparing itself for the liquid [r], the mouth can't help but tend towards producing a palatal fricative. Or perhaps the e after the c is "fronty" enough to produce palatalization. I don't know. But once you notice people saying "groshery," you start to hear it everywhere. And it begins to strike you as a form of gaucherie.

No better is "ashphalt." But here I think we are seeing folk etymology at work. In other words, some folks are a little stymied by the word asphalt (it is rather opaque), and since the stuff is sort of black and smelly, they have decided that the first syllable is really our friendly and familiar English word ash.

Incidentally, asphalt has been around in English since the 14th century, which is much earlier than I would have guessed. The OED cites John Trevisa's 1398 definition of Asphaltis: "glewe of Iudea is erthe of blacke colour and is heuy and stinkynge."

Folk etymology is a fairly common agent of linguistic change. Sometimes it happens when a word is introduced from a foreign language—the above is an example of this, as is sparrowgrass from asparagus.

At other times, a native word has an obsolete element no longer understood by speakers and another, more transparent form is substituted—for instance, bridegroom, from Old English brydguma (compare German Bräutigam), where the second element guma, meaning "man, hero," had ceased to be understood by the 16th century and was replaced by groom, meaning "lad." We might still be toasting the bride and goom if this hadn't happened!

Wednesday, May 5, 2010

Excrescent -t in Amongst and Whilst Part II

Against is one word in which the excrescent -t has become entirely standard. The Middle English form of the word had been aȝænes or aȝeins; thereafter, according to OED,

Late in the 14th century, after the -es had ceased

to be syllabic, the final -ens, -ains developed in the

south a parasitic -t as in amongs-t, betwix-t,

amids-t, probably confused with superlatives in -st

and c. 1525 this became universal in literary English.

This theory that prepositional forms were modelled after superlatives, i.e., that excrescent -t developed by analogy with -est forms, is interesting.

In particular, I'm inclined to think that the word next may have had an important role to play in this process. Most English speakers are now unaware of this, but next is a superlative. The Old English for "near" was neah; our positive form near is in fact the comparative form of neah; our present next developed from the superlative form neahst.

Next is also an adjective. But its meaning, having to do with relations of space and ordinality, is sort of quasi-prepositional. Perhaps the excrescent -t that became standard in the preposition against was bolstered by the example of next, especially as awareness of next's superlative nature waned in the minds of speakers.

So while (or whilst) it bugs me perennially that amongst and whilst are preferred by some writers over the manifestly briefer and morphologically "cleaner" among and while, I can certainly see why these forms were an inevitable outgrowth of amongs and whiles, especially as speakers of English began to lose their intuitive grasp of the adverbial genitive -s.

In sum, there were two (maybe three) factors that drove the development of forms like amongst and whilst. One, the tendency to sound a homorganic plosive after the [s]; two, the analogy of superlative forms, especially, perhaps, next; and, three, a grammatical uncertainty about -s endings and an impulse to make these words align with a better understood form.

Incidentally, the process continues today. I have heard a number of people say acrosst for across.

Late in the 14th century, after the -es had ceased

to be syllabic, the final -ens, -ains developed in the

south a parasitic -t as in amongs-t, betwix-t,

amids-t, probably confused with superlatives in -st

and c. 1525 this became universal in literary English.

This theory that prepositional forms were modelled after superlatives, i.e., that excrescent -t developed by analogy with -est forms, is interesting.

In particular, I'm inclined to think that the word next may have had an important role to play in this process. Most English speakers are now unaware of this, but next is a superlative. The Old English for "near" was neah; our positive form near is in fact the comparative form of neah; our present next developed from the superlative form neahst.

Next is also an adjective. But its meaning, having to do with relations of space and ordinality, is sort of quasi-prepositional. Perhaps the excrescent -t that became standard in the preposition against was bolstered by the example of next, especially as awareness of next's superlative nature waned in the minds of speakers.

So while (or whilst) it bugs me perennially that amongst and whilst are preferred by some writers over the manifestly briefer and morphologically "cleaner" among and while, I can certainly see why these forms were an inevitable outgrowth of amongs and whiles, especially as speakers of English began to lose their intuitive grasp of the adverbial genitive -s.

In sum, there were two (maybe three) factors that drove the development of forms like amongst and whilst. One, the tendency to sound a homorganic plosive after the [s]; two, the analogy of superlative forms, especially, perhaps, next; and, three, a grammatical uncertainty about -s endings and an impulse to make these words align with a better understood form.

Incidentally, the process continues today. I have heard a number of people say acrosst for across.

Wednesday, April 28, 2010

Excrescent -t in Amongst and Whilst Part I

Some writers prefer to use amongst and whilst to among and while. I'm not sure what drives this preference (do the -st forms sound more formal to some?), but the -t in these forms doesn't mean anything. The -s on the other hand is our old friend the adverbial genitive.

The -t is what historians of the English language call an excrescent -t. Excrescent means "superfluous outgrowth". A famous example of an excrescent -t is that in the word varmint, which is a dialectal form of vermin with a characteristically southern English lowering of er to ar (seen also in the development of varsity from university, and parson from person) and a final -t that means nothing whatever but is a mere outgrowth from the previous consonant [n].

Excrescent -t tends to develop after n and s. This is because, in forming the sounds [n] and [s], the tongue is already in a convenient position to produce a [t]. This is what's known as an intrusive homorganic plosive. "Homorganic" because the sounds [n] and [t] are produced with the tongue in exactly the same position (on the alveolar ridge just behind the top front teeth); a "plosive" is "a consonant sound made when a complete closure in the vocal tract is suddenly released" (David Crystal, An Encyclopedic Dictionary of Language and Languages). So by the time your tongue is in place to sound an [n], why not do a bit more and sound a [t], too? (The plosive consonants in English are, by the way, [p], [b], [k], [g], [d] and [t]).

Intrusive homorganic plosives are among my favourite phonological phenomena. The word mushroom, for instance, was sometimes spelled (and presumably pronounced) in the 16th and 17th centuries with a final [p], as in the forms moshrump, moushrimpe, mushrompe, and even mushrumpt (two excrescences for the price of one!).

While amongst and whilst exist as variants alongside among and while, against is one example of an excrescent -t that has become entirely standard. I'll write more about it in my next post.

The -t is what historians of the English language call an excrescent -t. Excrescent means "superfluous outgrowth". A famous example of an excrescent -t is that in the word varmint, which is a dialectal form of vermin with a characteristically southern English lowering of er to ar (seen also in the development of varsity from university, and parson from person) and a final -t that means nothing whatever but is a mere outgrowth from the previous consonant [n].

Excrescent -t tends to develop after n and s. This is because, in forming the sounds [n] and [s], the tongue is already in a convenient position to produce a [t]. This is what's known as an intrusive homorganic plosive. "Homorganic" because the sounds [n] and [t] are produced with the tongue in exactly the same position (on the alveolar ridge just behind the top front teeth); a "plosive" is "a consonant sound made when a complete closure in the vocal tract is suddenly released" (David Crystal, An Encyclopedic Dictionary of Language and Languages). So by the time your tongue is in place to sound an [n], why not do a bit more and sound a [t], too? (The plosive consonants in English are, by the way, [p], [b], [k], [g], [d] and [t]).

Intrusive homorganic plosives are among my favourite phonological phenomena. The word mushroom, for instance, was sometimes spelled (and presumably pronounced) in the 16th and 17th centuries with a final [p], as in the forms moshrump, moushrimpe, mushrompe, and even mushrumpt (two excrescences for the price of one!).

While amongst and whilst exist as variants alongside among and while, against is one example of an excrescent -t that has become entirely standard. I'll write more about it in my next post.

Wednesday, April 21, 2010

Volcano Causes Disruption in Speech Flows

When I checked a few minutes ago, the phrase "Eyjafjallajokull pronunciation" was the 79th most popular Google search going. I'm not sure how that compares to the rush for the definition of "transgression" after a certain pro golfer's personal confessions of a few months ago, but clearly, it isn't just air travel that the Icelandic volcano has disrupted.

Patrick Smith, who writes Salon's Ask the Pilot column, wrote last Friday that Eyjafjallajökull "can only be pronounced correctly after consuming at least six cocktails"; not content with that, he came back on Monday opining that it is "a word that looks and sounds like the alphabet exploded".

The New York Times characterized the name of the volcano as a "16-letter, six-and-a-half syllable, 47-Scrabble-point name". Actually, you can't play proper nouns in Scrabble, but the point is taken.

Anglocentric, histrionic, linguistic fright aside, perhaps it's not too much to observe that, in fact, Icelandic is as a written language much more phonetic than English. By that I mean that the relation between script and sound is more consistent in Icelandic than in our notoriously hard-to-spell-and-pronounce language.

The NYT's recommended "EY-ya-fyat-lah-YOH-kuht" is pretty close to the mark, but I also like the BBC's "AY-uh-fyat-luh-YOE-kuutl-uh", mostly because in specifying that that's "oe" as in French coeur, they haven't forgotten that the umlaut over the o in jökull indicates a rounded vowel. The BBC guide also recognizes that the double ll in this last element must be pronounced as [tl], just as in the middle element fjalla. That final l, by the way, should be articulated but not voiced.

If none of that makes much sense, you can hear a recording of the proper pronunciation here.

I was going to come on and pontificate about how eyja is cognate with island and fjall is related to the Yorkshire fell, meaning "hill" or "high moor", but I see that the work's already been done for me here (scroll down to the part in blue, by David Shaw).

So instead I'll just muse randomly about the double-l spellings. My hubby, who teaches Old Icelandic at the local university, tells me that as far as anyone knows, the -ll- in words like fjalla and jökull was pronounced as an extra long [l] — as in, say, pronouncing the name of Mel Lastman (with apologies to Torontonians for the reminder of our former mayor's existence).

Through a process of dissimilation (defined by David Crystal as "the influence exercised by one sound segment upon another, so that the sounds become less alike"), the first l in the pair became pronounced over time as [t].

Something very like this dissimilation is found also in Welsh, where ll is pronounced [chl] (ch pronounced as in loch), as in the place name Llandudno.

In French and Spanish, on the other hand, -ll- is pronounced as a glide (as though it were y), as in ville or quesadilla. But I've also heard some Spanish speakers (especially from Latin America) pronounce the double-l as a voiced palatal fricative [ȝ], as in the initial consonant of French jaune.

No grand point to make here — just enjoying the variation!

Patrick Smith, who writes Salon's Ask the Pilot column, wrote last Friday that Eyjafjallajökull "can only be pronounced correctly after consuming at least six cocktails"; not content with that, he came back on Monday opining that it is "a word that looks and sounds like the alphabet exploded".

The New York Times characterized the name of the volcano as a "16-letter, six-and-a-half syllable, 47-Scrabble-point name". Actually, you can't play proper nouns in Scrabble, but the point is taken.

Anglocentric, histrionic, linguistic fright aside, perhaps it's not too much to observe that, in fact, Icelandic is as a written language much more phonetic than English. By that I mean that the relation between script and sound is more consistent in Icelandic than in our notoriously hard-to-spell-and-pronounce language.

The NYT's recommended "EY-ya-fyat-lah-YOH-kuht" is pretty close to the mark, but I also like the BBC's "AY-uh-fyat-luh-YOE-kuutl-uh", mostly because in specifying that that's "oe" as in French coeur, they haven't forgotten that the umlaut over the o in jökull indicates a rounded vowel. The BBC guide also recognizes that the double ll in this last element must be pronounced as [tl], just as in the middle element fjalla. That final l, by the way, should be articulated but not voiced.

If none of that makes much sense, you can hear a recording of the proper pronunciation here.

I was going to come on and pontificate about how eyja is cognate with island and fjall is related to the Yorkshire fell, meaning "hill" or "high moor", but I see that the work's already been done for me here (scroll down to the part in blue, by David Shaw).

So instead I'll just muse randomly about the double-l spellings. My hubby, who teaches Old Icelandic at the local university, tells me that as far as anyone knows, the -ll- in words like fjalla and jökull was pronounced as an extra long [l] — as in, say, pronouncing the name of Mel Lastman (with apologies to Torontonians for the reminder of our former mayor's existence).

Through a process of dissimilation (defined by David Crystal as "the influence exercised by one sound segment upon another, so that the sounds become less alike"), the first l in the pair became pronounced over time as [t].

Something very like this dissimilation is found also in Welsh, where ll is pronounced [chl] (ch pronounced as in loch), as in the place name Llandudno.

In French and Spanish, on the other hand, -ll- is pronounced as a glide (as though it were y), as in ville or quesadilla. But I've also heard some Spanish speakers (especially from Latin America) pronounce the double-l as a voiced palatal fricative [ȝ], as in the initial consonant of French jaune.

No grand point to make here — just enjoying the variation!

Wednesday, April 14, 2010

Suffix-fu

A few weeks ago I was reading Andrew Leonard's column at Salon.com and came across the following sentence (about the new function for biking directions on Google Maps):

My hope is that a properly designed and administered

system will marry Google's algorithmic-fu with localized

human intelligence and, over time, we will get a platform

of bike-rich geography that just keeps improving.

Algorithmic-fu? A quick Google search ensued. It appears that -fu is a productive nominal suffix meaning something like "prowess." It is most heavily used by techies, hence such neologisms as metric-fu, emacs-fu, Script-fu, and gym-fu (a "fitness minigame" iPhone app).

There is also Google-fu (amusingly debated at this online forum), defined by a netizen as

the uncanny ability to hit on the right combinations of

words and phrases to make Google [hit on] a half-

remembered webpage that you saw once back in 2002.

Without question, the suffix -fu is from kung fu, a Chinese phrase that when used by English speakers refers only to the martial art made famous by David Carradine in that 1970s TV show. But kung fu in Chinese (gongfu in Mandarin, gang hu in my native Teochew) may be used of anything that is performed with great skill and/or labour.

Indeed, the first sense listed for gongfu in my Concise Oxford Chinese-English Dictionary is "time." You gongfu zai lai ba means "Come again whenever you have time". It is only senses 2 and 3 that define gongfu as "effort;work; labour" and "workmanship; skill; art" respectively.

And it is the gong element that does the heavy lifting, so to speak—this is the element that means "work," "worker," or "man-day" (whence the sense of time develops). Our -fu, on the other hand, means "husband" or "man."

So to be perfectly correct, we should be using Google-fu to mean "master of Google." Instead, we see it used to mean something like "(mysterious) power," as in My Darknet style Google-fu is more powerful than your Wetware style Google-fu (whatever that means).

By the way, the posters on Google-fu were all agreed that the -fu suffix had been introduced into English by Joe Bob Briggs. I had never heard of him (I do not get out much), but I now know that he is a film critic and comedian who would sprinkle -fu phrases throughout his reviews of B-horror movies.

My hope is that a properly designed and administered

system will marry Google's algorithmic-fu with localized

human intelligence and, over time, we will get a platform

of bike-rich geography that just keeps improving.

Algorithmic-fu? A quick Google search ensued. It appears that -fu is a productive nominal suffix meaning something like "prowess." It is most heavily used by techies, hence such neologisms as metric-fu, emacs-fu, Script-fu, and gym-fu (a "fitness minigame" iPhone app).

There is also Google-fu (amusingly debated at this online forum), defined by a netizen as

the uncanny ability to hit on the right combinations of

words and phrases to make Google [hit on] a half-

remembered webpage that you saw once back in 2002.

Without question, the suffix -fu is from kung fu, a Chinese phrase that when used by English speakers refers only to the martial art made famous by David Carradine in that 1970s TV show. But kung fu in Chinese (gongfu in Mandarin, gang hu in my native Teochew) may be used of anything that is performed with great skill and/or labour.

Indeed, the first sense listed for gongfu in my Concise Oxford Chinese-English Dictionary is "time." You gongfu zai lai ba means "Come again whenever you have time". It is only senses 2 and 3 that define gongfu as "effort;work; labour" and "workmanship; skill; art" respectively.

And it is the gong element that does the heavy lifting, so to speak—this is the element that means "work," "worker," or "man-day" (whence the sense of time develops). Our -fu, on the other hand, means "husband" or "man."

So to be perfectly correct, we should be using Google-fu to mean "master of Google." Instead, we see it used to mean something like "(mysterious) power," as in My Darknet style Google-fu is more powerful than your Wetware style Google-fu (whatever that means).

By the way, the posters on Google-fu were all agreed that the -fu suffix had been introduced into English by Joe Bob Briggs. I had never heard of him (I do not get out much), but I now know that he is a film critic and comedian who would sprinkle -fu phrases throughout his reviews of B-horror movies.

Wednesday, April 7, 2010

Future English: Previous and Next

I have noticed that, apart from pop-up ads and spam protection, email systems also differ in the way that they allow users to navigate back and forth through messages without returning to their inbox.

In my Gmail account, I have noted with approval that to get to a more recent message I click on "newer"; to get to a less recent message, I click on "older." This is very fine, and in keeping with Google's pledge not to be evil.

In my Yahoo and Fastmail accounts, on the other hand, "previous" means newer and "next" means older. In other words, previous means next and next means previous. This is perverse. It doesn't even make sense from a spatial point of view, because everyone knows that the newest message appears at the top.

I don't know if lexicographers of current English have picked up on this. But when I'm old and the barista at Starbucks says, "Can I help who's previous?", I'll know where it all began.

In my Gmail account, I have noted with approval that to get to a more recent message I click on "newer"; to get to a less recent message, I click on "older." This is very fine, and in keeping with Google's pledge not to be evil.

In my Yahoo and Fastmail accounts, on the other hand, "previous" means newer and "next" means older. In other words, previous means next and next means previous. This is perverse. It doesn't even make sense from a spatial point of view, because everyone knows that the newest message appears at the top.

I don't know if lexicographers of current English have picked up on this. But when I'm old and the barista at Starbucks says, "Can I help who's previous?", I'll know where it all began.

Wednesday, March 31, 2010

Toward or Towards Part V

Uh, maybe this blog isn't turning out to be as entertaining as I had envisioned. I seem to have strayed a long way from funny church signs and trivialities about a favourite food substance, but I promise (myself) I'll finish what I have to say about toward and towards here and move on to something more fun.

The adjectival and adverbial uses of toward/towards:

Toward was used as an adjective meaning "impending," as in There is sure another flood toward, and these couples are comming to the Arke (Shakespeare, As You Like It).

When used of young people, it meant "promising," as in There was never mother had a towarder son (Heywood, Edward IV Part I).

Toward could also mean "favourable," as in He too sends for the Greek ship a toward breeze (Gladstone, Juventus Mundi). Incidentally, about the only survival of this adjectival sense of toward in modern English is in the adjective untoward , meaning "awkward" or "unlucky."

The adverbial uses of toward/towards are not always easy to distinguish from the adjectival, but in the sentence A varlet ronning towards hastily (Spenser, The Faerie Queene), the word clearly functions as an adverb of direction.

One last thing: The adverbial forms of toward are not limited to the zero-derived or endingless toward and the genitive towards. There was also the (now obsolete) form towardly!

Happily, this series of posts is now hastening toward(s) a conclusion.

The adjectival and adverbial uses of toward/towards:

Toward was used as an adjective meaning "impending," as in There is sure another flood toward, and these couples are comming to the Arke (Shakespeare, As You Like It).

When used of young people, it meant "promising," as in There was never mother had a towarder son (Heywood, Edward IV Part I).

Toward could also mean "favourable," as in He too sends for the Greek ship a toward breeze (Gladstone, Juventus Mundi). Incidentally, about the only survival of this adjectival sense of toward in modern English is in the adjective untoward , meaning "awkward" or "unlucky."

The adverbial uses of toward/towards are not always easy to distinguish from the adjectival, but in the sentence A varlet ronning towards hastily (Spenser, The Faerie Queene), the word clearly functions as an adverb of direction.

One last thing: The adverbial forms of toward are not limited to the zero-derived or endingless toward and the genitive towards. There was also the (now obsolete) form towardly!

Happily, this series of posts is now hastening toward(s) a conclusion.

Wednesday, March 24, 2010

Toward or Towards Part IV

The OED, which is a historical dictionary (i.e., it lists all the forms and functions that a word has had throughout the history of the language) lists toward and towards as separate headwords. Indeed, there are two entries for toward—the first being the adjective and adverb and the second being the preposition. Towards has only one entry, as preposition and adverb.

In a visually more helpful way:

Now, both the adjectival and adverbial uses of toward and towards, respectively, have fallen out of use. (The Concise Oxford still has toward, adj., listed as an archaic form, but I for one am ready to call it obsolete.) Since both toward and towards also functioned as prepositions, what we have is a falling together of two separate words to perform one function, that of a preposition meaning "in the direction of."

So now we have:

And that's why modern English speakers are saddled with two variants. Toward and towards were originally two separate words performing closely related and overlapping functions. Only one of those functions remains in modern English, but both forms have survived. If you like, the -s form is a relic.

(Of course, many linguists would disagree that they were ever two totally separate words, but I don't want to get into the messy business of defining what a word is.)

And in case you are wondering how toward could ever have been an adverb without the -s ending, the OED states that "the advb. use appears to arise out of the predicative use of the adj., or from the neuter adj." That is, the word acquired an adverbial function without changing its form (a process that linguists term zero derivation).

(Another possibility: In Old English, adverbs were also formed with an -e ending, which disappeared in Middle English. This is why it is actually still possible to form adverbs with no adverbial ending per se, as in the phrase dead slow. Some self-appointed grammarians like to huff and puff about people who don't know the difference between adjectives and adverbs, but in fact the "endingless" adverb has a very long history in the English language.)

So, to summarize my posts so far: Which is correct, toward or towards? Both are correct. Is toward American and towards British? No, not really. Does the -s in towards mean anything? Yes.

What were some examples of toward as an adjective and toward/towards as an adverb? That's for my next post (which, I promise, is the last in this dull series).

In a visually more helpful way:

toward, adjective and adverb

toward, preposition

towards, preposition and adverb

Now, both the adjectival and adverbial uses of toward and towards, respectively, have fallen out of use. (The Concise Oxford still has toward, adj., listed as an archaic form, but I for one am ready to call it obsolete.) Since both toward and towards also functioned as prepositions, what we have is a falling together of two separate words to perform one function, that of a preposition meaning "in the direction of."

So now we have:

toward, adjective and adverb

toward, preposition

towards, prepositionand adverb

And that's why modern English speakers are saddled with two variants. Toward and towards were originally two separate words performing closely related and overlapping functions. Only one of those functions remains in modern English, but both forms have survived. If you like, the -s form is a relic.

(Of course, many linguists would disagree that they were ever two totally separate words, but I don't want to get into the messy business of defining what a word is.)

And in case you are wondering how toward could ever have been an adverb without the -s ending, the OED states that "the advb. use appears to arise out of the predicative use of the adj., or from the neuter adj." That is, the word acquired an adverbial function without changing its form (a process that linguists term zero derivation).

(Another possibility: In Old English, adverbs were also formed with an -e ending, which disappeared in Middle English. This is why it is actually still possible to form adverbs with no adverbial ending per se, as in the phrase dead slow. Some self-appointed grammarians like to huff and puff about people who don't know the difference between adjectives and adverbs, but in fact the "endingless" adverb has a very long history in the English language.)

So, to summarize my posts so far: Which is correct, toward or towards? Both are correct. Is toward American and towards British? No, not really. Does the -s in towards mean anything? Yes.

What were some examples of toward as an adjective and toward/towards as an adverb? That's for my next post (which, I promise, is the last in this dull series).

Wednesday, March 17, 2010

Toward or Towards Part III

The s-ending of towards is a suffix that forms adverbs, just like -ly. But unlike -ly, the -s suffix is a genitive ending.

What is a genitive? Roughly speaking, a genitive is a noun form that may be translated by the phrase "of the __."

For instance, the genitive form of the Old English noun stan (meaning stone) is stanes, meaning "of the stone." In modern English we no longer speak of the genitive but of the possessive. The possessive case is normally indicated with an apostrophe s (e.g., the cat's toy).

There are, however, many instances where an apostrophe s strictly indicates a genitive relation, not a possessive one. In the phrase a stone's throw, we are speaking not of a throw belonging to the stone but of a throw of the stone (the genitive expresses an object relation for the stone).

Adverbial genitives are -s endings or of a/the phrases that indicate an adverbial function. In a sentence such as Sundays my family goes to church, the -s on Sundays doesn't indicate a plural; it indicates an adverb (of time). That it is a genitive may be shown by the sentence My family goes to church of a Sunday, which is another way of saying exactly the same thing. Phrases such as of an evening or of a Sunday are becoming somewhat quaint in modern English, but they are genitives that express an adverbial function.

In some dialects of English, people say She's ages with him, with the meaning "she and he are the same age." In more standard English, the of form is preferred: She is of an age with him or They are of an age.

If this all seems impossibly archaic, then consider the expression I'm friends with him. The -s here isn't a plural (I'm a friend, he's a friend, we're all friends!), but an adverbial genitive. In this case, however, the of form doesn't seem to be in use.

The adverbial genitive -s is still alive and well. You can see it in usages such as You've got it backwards, Don't look sideways and in the words once, twice, and thrice (where it is spelled with a -ce).

I used to explain all this to some of my long-suffering co-workers at the press. But it never occurred to me (and I believe they were too polite to point out) that, of course, toward/towards isn't an adverb, but a preposition.

So why the adverbial -s? I'll write about that in my next post.

What is a genitive? Roughly speaking, a genitive is a noun form that may be translated by the phrase "of the __."

For instance, the genitive form of the Old English noun stan (meaning stone) is stanes, meaning "of the stone." In modern English we no longer speak of the genitive but of the possessive. The possessive case is normally indicated with an apostrophe s (e.g., the cat's toy).

There are, however, many instances where an apostrophe s strictly indicates a genitive relation, not a possessive one. In the phrase a stone's throw, we are speaking not of a throw belonging to the stone but of a throw of the stone (the genitive expresses an object relation for the stone).

Adverbial genitives are -s endings or of a/the phrases that indicate an adverbial function. In a sentence such as Sundays my family goes to church, the -s on Sundays doesn't indicate a plural; it indicates an adverb (of time). That it is a genitive may be shown by the sentence My family goes to church of a Sunday, which is another way of saying exactly the same thing. Phrases such as of an evening or of a Sunday are becoming somewhat quaint in modern English, but they are genitives that express an adverbial function.

In some dialects of English, people say She's ages with him, with the meaning "she and he are the same age." In more standard English, the of form is preferred: She is of an age with him or They are of an age.

If this all seems impossibly archaic, then consider the expression I'm friends with him. The -s here isn't a plural (I'm a friend, he's a friend, we're all friends!), but an adverbial genitive. In this case, however, the of form doesn't seem to be in use.

The adverbial genitive -s is still alive and well. You can see it in usages such as You've got it backwards, Don't look sideways and in the words once, twice, and thrice (where it is spelled with a -ce).

I used to explain all this to some of my long-suffering co-workers at the press. But it never occurred to me (and I believe they were too polite to point out) that, of course, toward/towards isn't an adverb, but a preposition.

So why the adverbial -s? I'll write about that in my next post.

Wednesday, March 10, 2010

Toward or Towards Part II

Some of the "folk" explanations I read of this variation were quite intriguing. (Most come from here).

One was quite refreshing in its consideration of phonological factors, but was unfortunately sort of crazy: "Perhaps, the British use an 's' ... because they pronouce [sic] the word with the accent on the second syllable (toWARDS). S makes an easier transition to the following word; whereas Americans say "TOward" and it flows more easily to the following word so that the 's' is unnecessary."

The British do use a linking r (as in the famous "lore-and-order" pronunciation of law and order), but no linking s that I'm aware of.

Some felt that toward was used with singular subjects and towards with plural subjects (e.g., He walked toward the water's edge vs. They walked towards the water's edge.) Others advocated the opposite (by analogy with third-person present verbal forms). Somewhat ominously, one person said they had been taught one or other of these theories in school and that their teacher had seemed very convincing.

An interesting comment was that towards sounded "backwoodsy." (Perhaps because the -s isn't perceived to be performing a function and therefore seems archaic or obsolete?)

This rant I found rather less interesting because it was so ill-tempered, but it does give the lie to the notion that towards is exclusively British:

I am sensitive about the distinction between

toward and towards because of an incident

involving the proofs of a book of mine being

published by Cambridge University Press in New

York. The copy editor, who seemed to be under

the impression that he/she had a better ear for the

English language than I do, consistently changed

my "towards" to "toward." Seemingly, the copy

editor took the s-less form to be more American-

sounding, but since I'm American I feel entitled to

make up my own mind (though I have to admit

that my mother is English, so maybe I picked up

the habit from her.) Anyway, I just strew "STET"

all over the manuscript to leave my version alone.

I am sensitive about the distinction between

toward and towards because of an incident

involving the proofs of a book of mine being

published by Cambridge University Press in New

York. The copy editor, who seemed to be under

the impression that he/she had a better ear for the

English language than I do, consistently changed

my "towards" to "toward." Seemingly, the copy

editor took the s-less form to be more American-

sounding, but since I'm American I feel entitled to

make up my own mind (though I have to admit

that my mother is English, so maybe I picked up

the habit from her.) Anyway, I just strew "STET"

all over the manuscript to leave my version alone.

Quite apart from the fact that the past tense of strew is strewed, this author also overlooks the possibility that the copy editor was following house style. All good editors do, even when they disagree with the style on specific points.

It all seems to boil down to the fact that most English speakers have lost a sense for how the -s is functioning in towards, and for that matter also in backwards, sideways, once, and widdershins.

I'll write about that in my next post.

I'll write about that in my next post.

Wednesday, March 3, 2010

Toward or Towards Part I

The style sheet at the publishing house where I worked for two years specified a preference for toward over towards. I followed the rule conscientiously, of course, but always felt that it was based on a misunderstanding of the -s form.

Now that I've had some time to read and Google around, I realize that 1) this misunderstanding is pervasive and various, and 2) I didn't know as much about this as I had first thought.

First, the misunderstanding: There seems to be widespread agreement that toward is American and towards is British, i.e., that the two forms function as regional markers. This notion is reinforced by Webster's Dictionary of English Usage and by the fact that both the Oxford Canadian Dictionary of Current English and Merriam-Webster list the s-less form first, while the -s form is listed as a variant. The Concise Oxford, on the other hand, does the opposite.

But in comments appended to the various blog posts on this matter, there were Americans who said they always said towards, Britons who said they always said toward, and Americans, Brits, and others who said they said both in free variation. I do not know if the Dictionary of American Regional English (DARE) will have anything to say on this matter when Vol. 5 (Sl–Z) is published this year.

This theory of regional variation even has embedded in it the notion that Noah Webster introduced the s-less form as a "simplified" form for American English. I thought this was implausible when I first read about it, but after consulting Webster's original dictionary I see he lists only the s-less form, even for the adverb (see 2 above).

Yet it seems clear that there is no transatlantic watershed dividing toward and towards in the same manner as, say, rubber and eraser or pants and trousers. Many people say both; and the ones who claim they always say one or the other often seem to have made up their own reasons for the choice.

I'll say more about "folk" theories of toward vs. towards in my next post.

Now that I've had some time to read and Google around, I realize that 1) this misunderstanding is pervasive and various, and 2) I didn't know as much about this as I had first thought.

First, the misunderstanding: There seems to be widespread agreement that toward is American and towards is British, i.e., that the two forms function as regional markers. This notion is reinforced by Webster's Dictionary of English Usage and by the fact that both the Oxford Canadian Dictionary of Current English and Merriam-Webster list the s-less form first, while the -s form is listed as a variant. The Concise Oxford, on the other hand, does the opposite.

But in comments appended to the various blog posts on this matter, there were Americans who said they always said towards, Britons who said they always said toward, and Americans, Brits, and others who said they said both in free variation. I do not know if the Dictionary of American Regional English (DARE) will have anything to say on this matter when Vol. 5 (Sl–Z) is published this year.

This theory of regional variation even has embedded in it the notion that Noah Webster introduced the s-less form as a "simplified" form for American English. I thought this was implausible when I first read about it, but after consulting Webster's original dictionary I see he lists only the s-less form, even for the adverb (see 2 above).

Yet it seems clear that there is no transatlantic watershed dividing toward and towards in the same manner as, say, rubber and eraser or pants and trousers. Many people say both; and the ones who claim they always say one or the other often seem to have made up their own reasons for the choice.

I'll say more about "folk" theories of toward vs. towards in my next post.

Friday, February 26, 2010

The Etymology of Ketchup

The Oxford English Dictionary has this to say about the etymology of ketchup:

app. ad. [apparently adapted from] Chinese (Amoy dial.)

kôechiap or kê-tsiap brine of pickled fish or shellfish

(Douglas Chinese Dict. 46/1, 242/1). Malay kechap (in Du.

spelling ketjap), which has been claimed as the original

source (Scott Malayan Wds. in English 64–67), may be

from Chinese.

In other words, the OED follows Douglas and Scott in assuming the first element of ketchup to be the Chinese word for fish. The actual definition of ketchup follows:

A sauce made from the juice of mushrooms, walnuts,

tomatoes, etc., and used as a condiment with meat, fish,

or the like. Often with qualification, as mushroom ketchup,

etc.

I've always thought this slightly strange. I know the relationship between a word and its referent is arbitrary, but why borrow a term meaning fish sauce to refer to a sauce made of mushrooms, walnuts, and tomatoes?

The Amoy dialect is a Hokkien (Fujian) dialect. I don't speak Hokkien but I do speak Teochew, a closely related Minnan dialect. In Teochew, the word for fish is heu (following the peng im system of romanization as explained at Gaginang.org) ; the word for juice or sauce is jap. But as far as I know, nobody says heu jap for fish sauce. Instead, the online dictionary at Gaginang.org suggests heu jui or heu lou.

On the other hand, the Teochew for tomato is ang mo gio. The last element, gio (Mandarin qié), means eggplant—an ang mo gio is a Westerner's eggplant. I don't know how I would prove it, but doesn't it make more sense for us to think of ketchup as evolving from gio jap?

In case you've glazed over while reading this and are thinking fondly of the stuff itself, I can recommend a highly entertaining chapter in Jeffrey Steingarten's The Man Who Ate Everything (Vintage, 1998) in which he embarks on a quest to find the world's best ketchup, even if he has to make it himself.

app. ad. [apparently adapted from] Chinese (Amoy dial.)

kôechiap or kê-tsiap brine of pickled fish or shellfish

(Douglas Chinese Dict. 46/1, 242/1). Malay kechap (in Du.

spelling ketjap), which has been claimed as the original

source (Scott Malayan Wds. in English 64–67), may be

from Chinese.

In other words, the OED follows Douglas and Scott in assuming the first element of ketchup to be the Chinese word for fish. The actual definition of ketchup follows:

A sauce made from the juice of mushrooms, walnuts,

tomatoes, etc., and used as a condiment with meat, fish,

or the like. Often with qualification, as mushroom ketchup,

etc.

I've always thought this slightly strange. I know the relationship between a word and its referent is arbitrary, but why borrow a term meaning fish sauce to refer to a sauce made of mushrooms, walnuts, and tomatoes?

The Amoy dialect is a Hokkien (Fujian) dialect. I don't speak Hokkien but I do speak Teochew, a closely related Minnan dialect. In Teochew, the word for fish is heu (following the peng im system of romanization as explained at Gaginang.org) ; the word for juice or sauce is jap. But as far as I know, nobody says heu jap for fish sauce. Instead, the online dictionary at Gaginang.org suggests heu jui or heu lou.

On the other hand, the Teochew for tomato is ang mo gio. The last element, gio (Mandarin qié), means eggplant—an ang mo gio is a Westerner's eggplant. I don't know how I would prove it, but doesn't it make more sense for us to think of ketchup as evolving from gio jap?

In case you've glazed over while reading this and are thinking fondly of the stuff itself, I can recommend a highly entertaining chapter in Jeffrey Steingarten's The Man Who Ate Everything (Vintage, 1998) in which he embarks on a quest to find the world's best ketchup, even if he has to make it himself.

Monday, February 22, 2010

May As Well Start With Some Piety ...

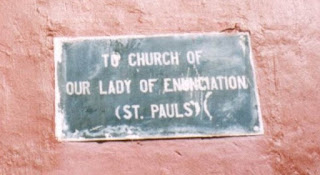

I'm sure the BVM spoke very properly, but this sign (in Malacca) still amused me very much.

I'm sure the BVM spoke very properly, but this sign (in Malacca) still amused me very much.When I was a schoolteacher, one of my colleagues set her class an English composition exercise on "What My Family Does On Sundays".

A student's piece began:

My family goes to mass every Sunday. My church is called Our Lady of Perpetual Sucker.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)